Air and Light by Caspar David Friedrich

Between Worlds1 Caspar David Friedrich’s Grosse Gehege or Large Enclosure The World Upside Down

The setting sun illuminates a patchy river landscape. A boat sails around the small clods of earth that project above the water’s surface. The reflections of the sky and the landscape in the tranquil water endow the image as a whole with a luminous quality.

As placid and idyllic as The Grosse Gehege near Dresden appears at first glance, it actually turns our world upside down. Painted by Caspar David Friedrich (1774–1840) in 1832, it is regarded today as the summit of his late work. The key lies in the image’s multi-perspectivity – it is not based on a single point of view. Friedrich’s complex composition is difficult to take in as a whole, and hence creates a sense of uncertainty with which the painting still moves viewers even after 200 years.

The Grosse Gehege is…

The Grosse Gehege is among the most radical works created by Friedrich – or for that matter, by any artist of the period. Could this explain its enormous popularity today?

Cultural studies expert Eva Horn, for example, believes that this painting calls into question the organization of our world as a whole. For Horn, The Grosse Gehege mirrors the instability of our contemporary environment, shaped to an increasing degree by human activity.

In the early 2000s, it was precisely the far-reaching impact of humanity on the environment that led natural scientists to proclaim the emergence of a new geological epoch: the Anthropocene. As the name suggests, the influence of human activity on the natural environment is no longer local or small-scale, and has now become global in scope. These effects include climate change, the increased species extinctions, and the far-reaching transformation of the land into a ‘man-altered landscape’. Researchers place the beginning of the Anthropocene around 1800, at the time of the Industrial Revolution. The Grosse Gehege dates from around this time.

Horn believes that the Anthropocene is intimately bound up with the failure of humanity’s collective imagination to grasp climate change – especially our part in it – but also the Earth itself in all of its complexity. She believes that these ideas are reflected in Friedrich’s Grosse Gehege: no longer can either the artist or the beholder grasp the world with the senses or the intellect, whether by capturing it on canvas or by comprehending it in its entirety. And Friedrich was among the first to visualize this realization.

What can Friedrich’s The Grosse Gehege tell us about the Anthropocene?

2 A Question of Perspective The Artistic Gaze

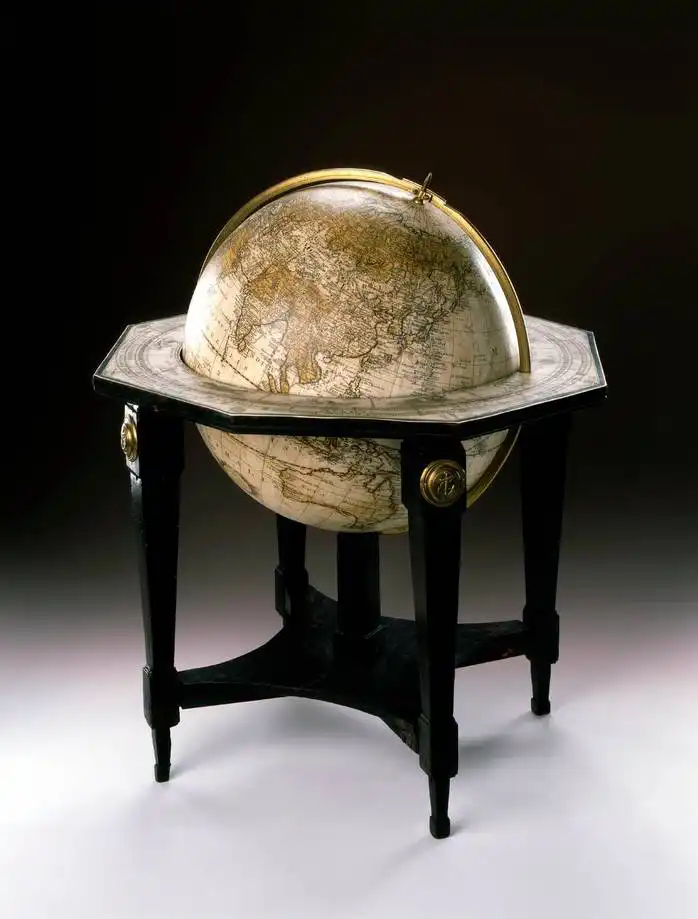

Johann Georg Klinger, Terrestrial Globe, Nuremberg, 1792, Mathematisch-Physikalischer Salon

With its vast, expansive sky and seemingly convex watery landscape, The Grosse Gehege has a strangely mesmerizing effect. Today, in an era of aviation and aerospace, it is reminiscent of a view of the Earth from outer space. In Friedrich’s time, such a view was still unimaginable.

All that was available at that time were models of the Earth as a globe, pieced together from many separate maps. Moving bodies of water and atmospheric cloud vortices, which we know from satellite images, were not represented on globes.

In response to the modern recognition that the Earth is a sphere and part of a cosmic system which aligned with the sun, terrestrial globes began to appear increasingly in the 15th century.

The first photograph of Earth seen from outer space, taken in close proximity to the moon.

NASA/William Anders, Earthrise, 24 December 1968, public domain.

In 1968, humans got to see for the first time what Earth looked like as a planet, as a ‘blue marble’. It finally became clear that man is not the center of all being, but only one actor among many, who bears responsibility for the habitat Earth with his actions.

Friedrich could not yet see the Earth from above or from outer space. Around 1800, initial views of one’s surroundings were made possible by ascending (church) towers and by the first hot-air balloon rides. Before the invention of photography, panoramas (some installed as giant walk-in spaces) left a lasting impression on spectators. In creating The Grosse Gehege, Friedrich may have drawn inspiration from such spectacular prospects.

It is now regarded as likely that in some instances, Friedrich used technical aids in his work as an artist. Practical guidance was probably provided by texts by the French art theorist Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes, for example. In Élémens de perspective pratique (1799/1800, translated into German three years later), Valenciennes recommends the use of instruments such as the telescope, sighting frame, and camera obscura in order to better capture perspectives or recognize colors more clearly.

Carl August Richter’s circular panorama of the view from the tower of Dresden’s Frauenkirche also displays a curving section of the Elbe River to the west of the city, whose bend encloses Ostragehege (›Ostra Enclosure‹).

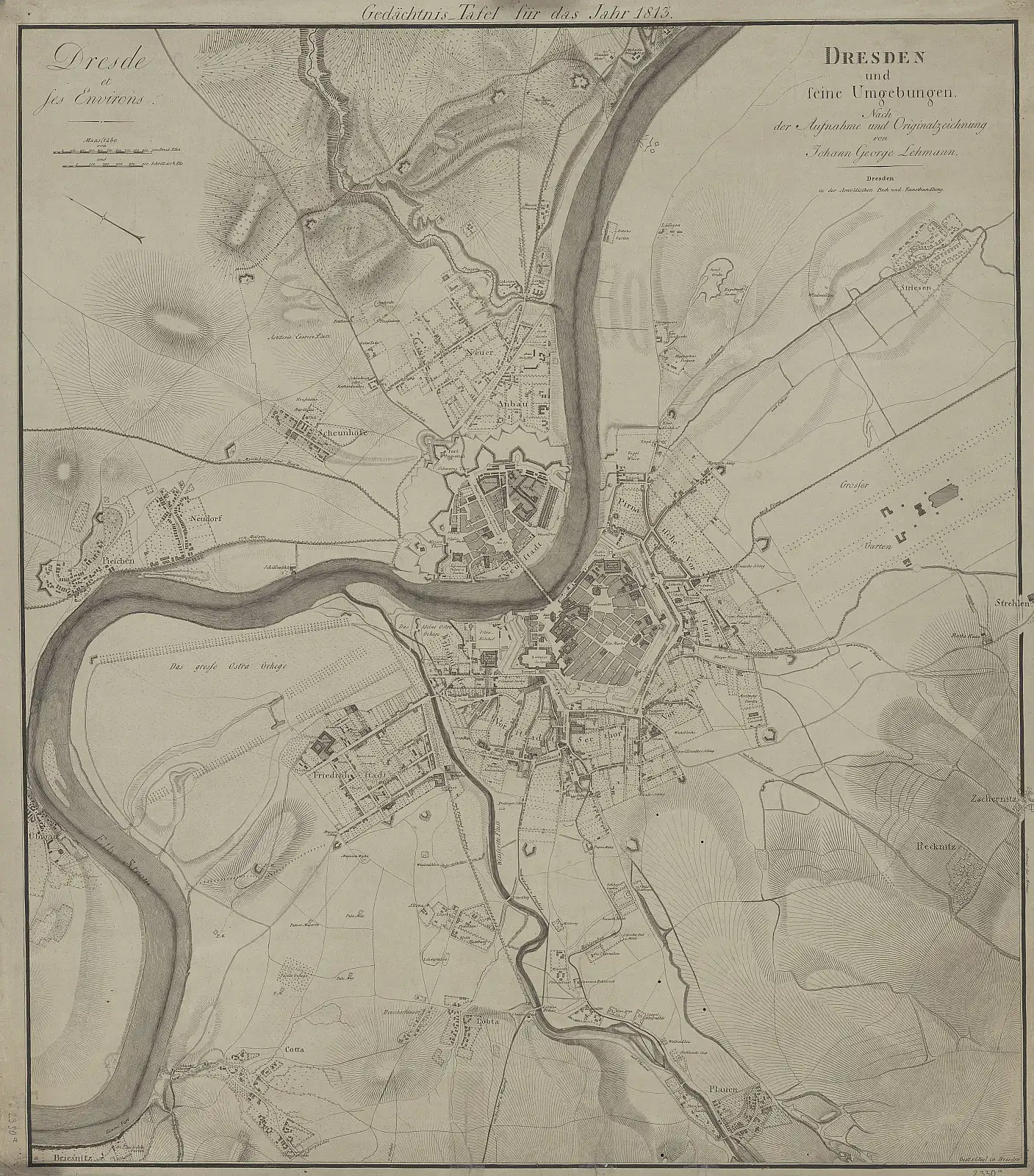

Historical Map: Dresden and surroundings, 1813

3 Friedrich’s View of the Grosse Gehege near Dresden The Elbe in Sight

In this area, located west of Dresden, Friedrich executed a number of drawings in 1804. In addition to Ostragehege, there are views of Pieschener Allee and the slopes of the Elbe in Radebeul. Nearly 30 years later, Friedrich assembled a number of motifs derived from this stock of drawings, combining them into a new whole in The Grosse Gehege.

Centuries before, the wet landscape of Ostragehege, with its meadows and rows of trees, had provided the Dresden court with agricultural produce.

In the late 17th century, a portion of this territory was enclosed for the purpose of keeping livestock; hence the name Gehege (meaning “enclosure”).

The avenue known as Lindenallee (›Linden avenue‹), shown on the image on the left, still exists today. A few of the original trees, planted around 1725, are still present: they have meanwhile reached an age of 300 years.

That Ostragehege looks so different now than it does in Friedrich’s Grosse Gehege is also an indication of the Anthropocene age: in order to improve navigability on the Elbe, man has changed the course of the river several times since the middle if the 19th century. The river was both deepened and narrowed. The aim was to prevent low water and to facilitate tourism and trade.

View across the Elbe from Pieschen. Recognizable upriver, toward the southeast, is Dresden, while on the opposite riverbank, toward the south, is Ostragehege, with Lindenallee.

Holger Birkholz, Senior Conservator at Albertinum, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden (German)

Holger Birkholz on Ostragehege near Dresden and The Grosse Gehege by Caspar David Friedrich (transcript)

»We are now in Pieschen on the Elbe. Visible in the background is the Dresden skyline. We have come here in order to gain an impression of what Caspar David Friedrich sought to depict in his painting The Grosse Gehege of 1832. We do not see Dresden itself, but Ostragehege is recognizable on the riverbank opposite. It was referred to as a Gehege [enclosure] because it was also used for livestock farming, as well as for hunting. And clearly visible on the other side of the Elbe are the Linden trees standing on the so-called Pieschener Allee, which were planted in the early 18th century. Which means that a few of these trees are nearly 300 years old.

When Friedrich went hiking here and captured a number of separate motifs in drawings, this avenue was just 100 years old, which is why it appears much less established in the painting and drawing. Interestingly, when we stand here, the landscape is far more expansive, is far broader. And the particular impression generated by the painting for us today, this unconfined extension of the landscape, is actually a phenomenon produced by optical compression.«

More important to Friedrich then an accurate representation of the location was nature’s impression on the artist – his sentiment, as he wrote:

It is not the artist’s task to produce a faithful depiction of atmosphere, water, rocks, trees.

Instead, the picture should mirror his soul, his sentiment.

This can also be seen in the sunset in The Grosse Gehege: in reality, the sun would set further west near Radebeul. To create an evening atmosphere, Friedrich altered the light source and incidence of light in his picture.

4 The Invisible Air and Light

In The Grosse Gehege near Dresden, the sky occupies more than half of the picture surface. In 19th century Germany, the terms »sky« (Himmel) and »light« (Licht) were relatively uncommon; instead, one spoke of »air« (Luft). And it is this that explains the following characterization of Friedrich’s art:

Not a landscape [Landschaft], but instead an airscape [Luftschaft]

Friedrich’s painted sky appears infinitely light – but is actually an element in a complex pictorial composition:

Both the watery landscape and the sky appear curved, as though viewed through a distorting mirror or fisheye lens. Perceptible here is a tension between these pictorial components, almost as though they were converging toward one another.

Where is the standpoint of the artist and the beholder located within the image?

The standpoint from which we observe the landscape remains indefinite. Rather than immersing the viewer in the landscape, the perspective is slightly elevated. This allows Friedrich to create a sense of distance between beholder and image; we are made aware of its technical artifice.

5 Off to New Shores The Human Presence in The Grosse Gehege

In The Grosse Gehege near Dresden, human existence becomes noticeable only upon closer viewing.

The little boat is a so-called Kaffenkahn, a transport barge. Readily visible here is the square sail, which billows out in the wind. In Friedrich’s time, the Kaffenkahn was a prevalent means for conveying a variety of commodities, especially timber from Saxon Switzerland, but also vegetables from Bohemia. In Dresden, such vessels landed directly before Friedrich’s house, located at An der Elbe 33.

A comparison between various roughly contemporary works of art shows that the so-called Kaffenkähne were an everyday sight on the Elbe at that time.

Trade routes such as the Elbe facilitated a form of globalization that was imperialistic in character. Without being aware of the implications of the exploitation of natural resources and the natural world, Western civilization of the early 1800s laid the groundwork for the Anthropocene age. With the inception of industrialization around 1800, CO2 levels rose significantly worldwide.

6 Friedrich’s Glimpse of the Anthropocene Between Worlds

Art before 1800 pictured the natural world as a contained and clearly delimited realm. But things are very different in Friedrich’s The Grosse Gehege:

What is brilliant about this painting is the way it marks the instability of every point of view [of] the world.

With the Great Enclosure, the great impossibility […] is believing that Earth can be gasped as a reasonable and coherent Whole…

Current research into the works of Caspar David Friedrich benefit from an awareness of global developments taking place during the 19th and 20th centuries. Friedrich’s contemporaries must have had their difficulties with The Grosse Gehege – its tense perspectival construction was simply too strange.

Unlike the other landscape painters of his time, Friedrich took as his subject not nature itself, but rather the human view of it.

The Grosse Gehege condenses an essential aspect of Friedrich’s conception of art and of the image:

pictures should allow us to experience with their inherent, inner-pictorial visual resources

what must inevitably elude human thought and knowledge.

Caspar David Friedrich’s pictures show us nature in a way we find difficult to comprehend, even today. Not unlike the complex interrelationships found on the Earth and the interdependencies existing between diverse actors, which we can never fully understand.

And it may be that The Grosse Gehege near Dresden contains more hints about the new age than Friedrich himself could have possibly realized.

I love it! Despite its age, this painting seems incredibly modern 😍